Q&A with Portugal's Former Minister of Education

Insights into a widely successful temporary program and how Portugal can once more achieve outstanding results for students.

I recently came across an interesting case study of Portugal’s educational program and the reforms that were introduced there from 2003 to 2015 and its subsequent results in elementary and middle-school students. The Portuguese Mathematical Society joined this effort and helped in the creation of a new math program and standards. The results observed in Portuguese students in the PISA assessment were so significant that 4th-grade students ended up surpassing their counterparts in Finland, a feat that had not been accomplished prior or since. The reforms implemented were extinguished shortly after when a new government was elected and subsequently a deterioration of academic performance took place among students.

Those findings were documented by Nuno Crato in his paper “Math Curriculum Matters” which was published this year in the European Mathematical Society’s Magazine. It is currently accessible online as open access, you can read the full paper here.

Nuno Crato was Portugal's Minister of Education and Science from 2011 until 2015 and was appointed as a nonpartisan cabinet member after a career as a college professor in Mathematics and Statistics and as a researcher in applied probability and time series models. He is currently at the University of Lisbon and Iniciativa Educação. He has authored several books on the topics of science popularization, education, and mathematics, and is a leading voice in the search for better educational models and approaches, especially as it pertains to mathematics.

I am thankful for his time and thoughtfulness in answering my questions. Initials are used in place of names for the sake of brevity, NC stands for Nuno Crato and LL for me.

LL: The paper you authored is quite interesting and provides a window into how fast one can see results from well-implemented education policies. It is quite unfortunate that it was only briefly lived. In the 2016's the Portuguese education ministry eschewed the previous educational standards that were goal-focused, clear, and much more structured, and in which you played a crucial role, correct? What inspired you to write this specific analysis now?

NC: Yes. After the 2015 elections, a new parliamentary alliance with the socialists, the communists, and a radical left party, supported a new government and eliminated much of the reforms the previous social-democrat government had introduced.

Although I’m an independent, I was appointed Minister of Education and Science in this social-democrat government. During the years 2011-2015, we introduced a set of reforms that were conscious, deliberated, and based both on science, namely on results from the economics of education and cognitive psychology, and on almost two decades of Portuguese experience in the fight to improve students real results.

The specific analysis now published by the European Mathematics Society Magazine had to wait for the publication of the 2019 TIMSS results (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) and went through the usually slow scientific journals’ publication process (reviewers, etc.). However, I’ve published previously a couple of articles and book chapters on the Portuguese experience. I suggest, for instance, you browse through the international book I edited in Springer. It’s titled “Improving a Country’s Education” and it’s open access, so you can download and read it in its totality or just choose the chapters you prefer.

LL: This abandonment of the previous standards in favor of an excessively unclear and lax model, was justified by the assumption that having high expectations for students would hurt disadvantaged students most, who will not be able to catch up - So, as a consequence, the standards and expectations were lowered for every Portuguese student.

NC: Yes, that’s true, but the effect depended on the schools and teachers. For a few years, some schools decided to stay with the previous standards, while others chose the less rigorous approach recommended by the new ministry. However, we have a very centralized school system. This means that the recommendations and directives issued from the ministry are eventually enforced by the national inspectorate body.

All this is paradoxical from my point of view. What a ministry should essentially do is to establish standards and promote a standardized assessment system, i.e., to establish goals and evaluate results. The new policy aimed to remove clear goals and have only fuzzy recommendations, while eschewing the evaluation, i.e., the policy is to avoid clear goals and clear evaluations but to control the processes.

LL: And what was the effect on schools and students, eventually?

NC: The effect was very clearly seen through the PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) and TIMSS evaluations, as these are the only reliable evaluation tools now existing for students’ knowledge and skills, after the exams and regular end-of-cycle standardized low-stakes assessments were abolished.

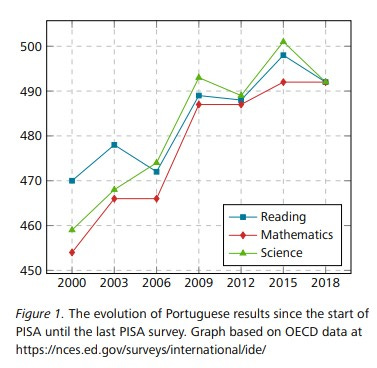

PISA and TIMSS both showed that Portuguese students improved continuously from 2002/2003 up to 2015, and then regressed. In 2015, our students achieved the best results ever in PISA and TIMSS.

For the first time, portuguese students surpassed the OECD average (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) in all areas. In TIMSS 4th grade math, our students got better results than many usually better performing European countries such as Finland.

In 2018 PISA, the results went visibly down. In TIMSS, we had a substantial fall. Although Finland also fell, we fell more and got results now below Finland and even below those we obtained in 2012.

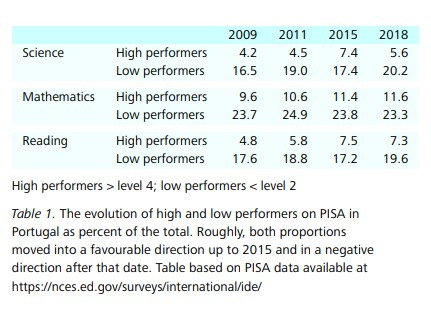

What I think is also very telling is the fact that with higher expectations, a more demanding curriculum, and standards, and with a more strict assessment, including exams, the number of low performers was substantially reduced. Later, with lots of fuss about reducing inequalities and protecting the disadvantaged classes, the number of low performers increased substantially. All this, with tables and hard data, is explained in my paper.

LL: In the U.S., we see the same phenomenon happening, often named "the bigotry of low expectations". In major cities such as New York and Los Angeles, many gifted student programs have been closed permanently, as to not make any student who couldn't get in feel less. As a result, there is an active societal pressure for students to not perform at their best, almost as if we are encouraging being average. Has the same phenomenon reached Portugal and if so, how can we return to a path where students are encouraged to excel academically?

NC: Portugal has a highly centralized system. So, a general change has to wait for a change in government policy, which I don’t believe will happen in the near future.

LL: In your paper you mention "school autonomy with incentives tied to students’ results", how did this work, considering that Portugal educational system is mostly public and government-run? Do local schools get rewarded according to how well their graduates score?

NC: In our 2011-2015 system, schools that could prove they used wisely additional resources got added resources, such as more teachers or supplementary teacher hours. The policy was very clear: if they improved students’ results with these additional resources, they kept getting more resources.

There are two important points here. First, we had to measure the improvements through a complex system of indicators, namely, internal students’ evaluations improvement, and not only their levels or retention reductions, but the alignment of all this with external evaluations. This created incentives for real improvement.

It’s not enough to have good student grades at national evaluations, we have to make sure at the same time there is a reduction in failing students so that schools don’t select only the best students to progress and be evaluated. It’s not enough to have good internal grades – these grades have to be confronted with national exam results. This way, schools had a disincentive to improve artificially internally attributed grades. The math of all this was a bit sophisticated, as the importance given to all these factors had to be fine-tuned nationally.

Second important point, the most important factor is the value-added, i.e., how schools improve their students’ real results. This is the way to be socially fair, as we know that one of the statistically most significant factors for students’ results is their socio-economic-cultural family background. It is very clear to me that all this can only work with two basic things in place: A well-designed, content-rich, ambitious and clear curriculum, and a national system of standardized assessment. Everything starts with the curriculum, and everything has to be assessed.

LL: Vocational high-school paths, as mentioned in your paper, are also becoming increasingly popular in the U.S, we call them Trade Schools. How well do these vocation school graduates do economically in the Portuguese job marketplace, when compared to their counterparts that finished university?

NC: There is huge variability. Some vocational paths are well built, they have the cooperation of specific industries, and address real shortages in the market. Others, go the simple path of offering whatever they have more readily available and don’t pay much attention to the labor market needs. I think cooperation from the start with the industry is crucial.

LL: One would be remiss to not mention that the Asian countries that often rank well in PISA have a common transversal ethos of discipline, perseverance, and over-achieving. No curriculum, no matter the quality of it, can match the drive these students have. What is your opinion on this?

NC: I think in Europe and in the so-called Western countries, we can approach Singapore and other Asian countries. See the case of Estonia.

LL: Are you hopeful for the educational future of Portuguese students?

Yes, but we have to press for a change in government policy. With our system, there is no other way for the population in general. Richer families can send their kids to selective private schools, and they are increasingly sending them to selective international schools. International schools are blooming in Portugal, and not mainly with foreign students. One of the reasons rich families chose international schools is those don’t have to abide by the fuzzy curriculum the ministry tries to impose on public schools.

LL: Finally, where can people read and follow your work?

NC: I try to keep my website updated, but I’m always late in this regard. It’s www.nunocrato.org At Academia.com, I also try to post most of my articles and presentations. I am also on Twitter and on Youtube.