“Intellectual” is a term used to describe someone who engages in critical thinking and who reflects at great lengths about reality and society, and as such, obtains public notoriety often being considered an authority on a specific topic or subject. The term was initially used around the 19th century with marked disdain to refer to a ruling elite class that had an instrumental power over politics and the shaping of culture. In Tsarist Russia, the term intelligentsia arose to refer to a class of individuals who were university-educated and whose critique, analysis, and reflections shaped the whole of society from politics to policy to the arts and culture; the term was also used in Europe to refer to people whose occupation was predominantly intellectual as opposed to being manual labor-oriented.

Currently, intelligentsia is most frequently employed as a derogatory term to refer to formal or informal policymakers, who have the authority to make decisions or influence decision-making for societies at large, often with little consideration of the feedback from the population impacted by such decisions. The historical malfeasance of notorious intellectuals should therefore be acknowledged. Such is the case with Jean-Jacques Rosseau, whose education theory places an emphasis on allowing children to express themselves freely without any constraints. This Rosseuan theory is remarkably present in our western society and in school philosophy, and yet, the irony that Rosseau abandoned all of his own children at an orphanage soon after their birth, is lost on most proponents of his ideas, which should at minimum encourage a healthy debate about the morality of his character and how it could affect the merits of his educational theory. This, among others, is indeed a clear case of the intelligentsia operating in its worst form, laden with hypocritical behavior that is often contrary to their own hypothesis and conjectures.

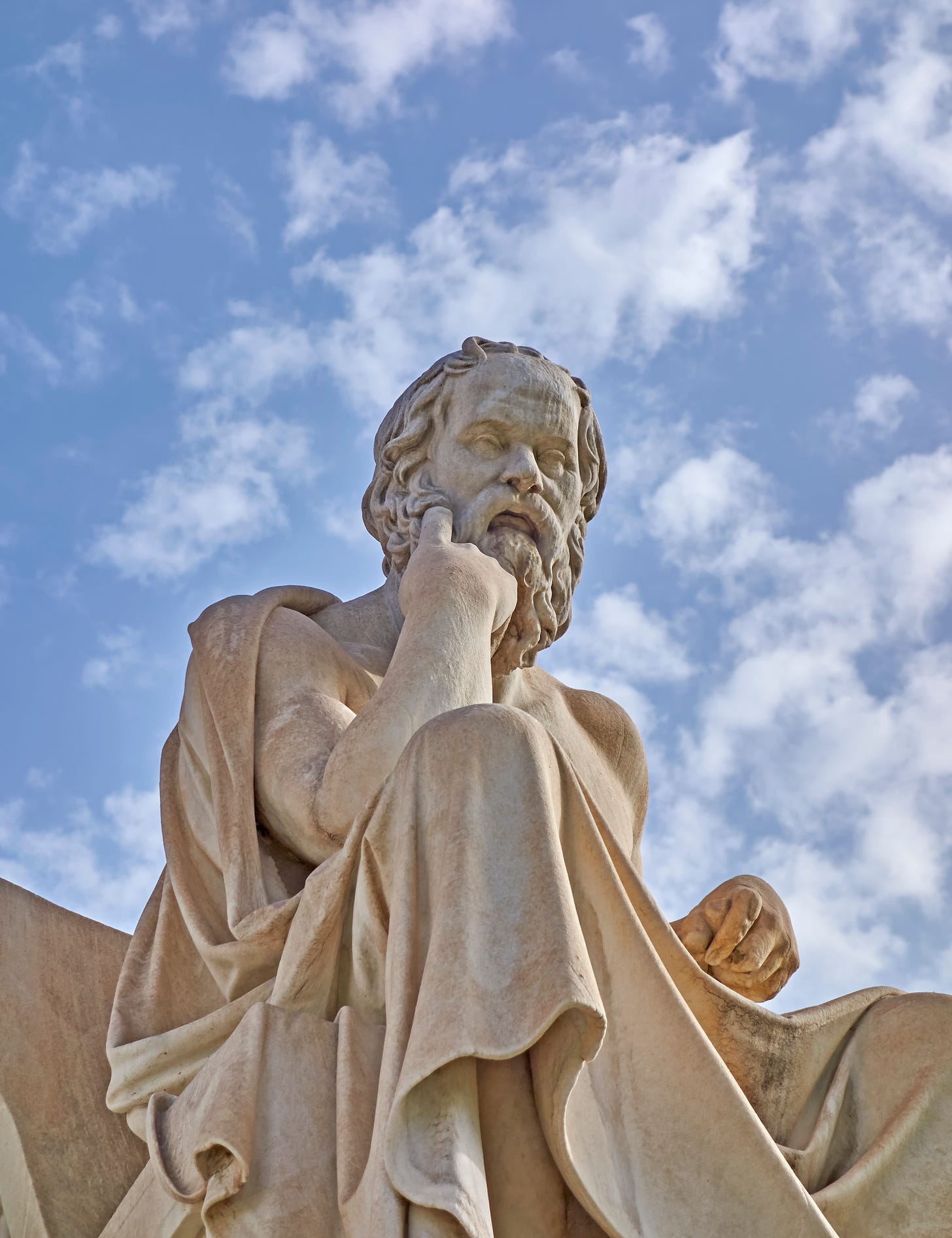

Therefore, I use the term “intellectual” loosely because of its ease of understanding, but perhaps the most adequate term should be intellectualism. Which I hesitate to use since that term is not easily recognizable. Intellectualism is a philosophical perspective on life that emphasizes the use of critical thinking and knowledge derived from reason, which is utterly the objective of pursuing an intellectual life. Now, it’s important to ground this pursuit in common sense and not get swept away in a hodgepodge of theories and postulations. Simply because one decides to embark on a life of intellectualism does not mean that the future holds a noble prize or any laureate, nor should this be the root cause for wanting to live a fuller intellectual life.

The love of knowledge, reviving and pursuing curiosity, and a longing to understand deeper truths of life, are often at the heart of people who consciously choose to lead an intellectual life. Most people are naturally curious and have felt this way in different periods of their lives, especially during childhood, but more often than not, we get swept away in obligations and responsibilities, all of which are valuable and can absolutely coexist with a more studious optic on life. Some of us have a natural inclination and devotion for learning, there’s a spark of innate curiosity that is propelling that craving to constantly keep enriching our minds and intellect with new information, new stories, and new perspectives. If you are one of those fortunate few, this occurs effortlessly. Regardless of the natural disposition to enjoy learning or not, there are behaviors that can be taken to improve our intellectual life, that won’t require enrolling in any university or study program.

A more in-depth intellectual life can be achieved by a series of choices and decisions that are made to alter our behavior and habits. These habits can be more or less challenging depending on how much one needs to adjust to get there.

Read. Then read some more. Real books. It is not possible to overstate the importance of reading. What you read informs your thoughts, and your thoughts will inform your actions and decisions. Reading a book is immensely different than reading something online like commentary or a small article since it requires greater focus and emerges the reader in the theme or plot of the story eminently more. Do not limit yourself to just fiction or non-fiction, the same way you breathe with both lungs, so both genres will add value to your intellect. “It is what you read when you don’t have to, that will determine what you will be when you can’t help it” - Oscar Wilde

Know thy limits. You have limited intellectual bandwidth each day. Use it wisely or the days turn into weeks that turn into months, in other words, prioritize your time and stop engaging in activities or behavior that are counter-productive to your goals.

Explore the unfamiliar. Start with smaller chunks of information regarding the theme you want to learn and then progress to greater challenges and do not be intimidated by lack of knowledge or familiarity with specific themes. Curiosity begets learning, which begets knowledge.

Let go of distractions. No, you cant have the cake and eat it too and whoever tells you otherwise is not being straightforward. Leading a purposeful intellectual life means you probably won’t know about the latest Netflix series and that’s fine, less time devoted to screens means more time reading. The learning and knowledge one gets from that time are invaluable, so much more than any TV series could ever be.

Be humble. In leading an intellectual life and pursuing topics on a deeper level you will inevitably realize you were wrong and you knew very little - that’s the perfect place to start learning. Be encouraged that you made the decision and recognize that every step eventually will make a mile.

Acknowledge your choices. Being succinct and precise in what behavior you’ll stop doing and which behavior you’ll engage in will set the pace for long-term success. Some examples are: I’ll read 20 books this coming year; I won’t commit to any TV shows at all; I won’t waste time pointlessly scrolling through my phone unless I have a specific reason to use my phone; No screens after 7 pm; always read before going to sleep.

Look back in time. Examples and inspiration of people who purposefully try to lead such a life don’t abound in our distraction-filled modern times. However, there are plenty of examples in a not so distant past of great men and women, whose dedication and perseverance can uplift anyone.

Lead your children and family. If you don’t have anyone around you that pursues a richer intellectual life, then become one yourself and lead, it will benefit your kids immensely. Children learn by example, even if it seems like they have zero interest in reading now, in time they will come around, remember your habits and follow in the same footsteps.

Unlike most new-year goals, which are temporary and short-lived, you are best suited looking at this as a way of life, a change in personality and habits that hopefully will be everlasting. Clearly, it does not mean that your life will be meticulously organized and without setbacks. Life happens and the unexpected is certain to happen at times, but still, in those times, there is the recognition that a return to a previous good rhythm is absolutely necessary, one that is rooted in the pursuit of all that is true, good and beautiful, one that is undoubtedly aimed at making life as fulling and enjoyable as it should be.

On reading books - regularly and with variety - I am also convinced of its necessity, especially in the current information landscape where most people are stuck in the equivalent of a media particle accelerator.

While researching for my next article, I came across this quote in Neil Postman's 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death:

"What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism."

Postman argued in the book that society was most likely heading towards a Huxleyan world. That the rapid technological shift, notably from print to television, had already shifted the information paradigm towards an entertainment-centric information landscape.

Fast forward to the 2020's, Postman's position is still valid but we have also seen Orwellian tendencies on top of it all; censorship, historical revisionism, books removed from schools, and the like.

Even though the future looks bleak sometimes, I am still hopeful that there is an appetite in our societies ready for an intellectual renaissance.

I loved this article, thank you! You touch on something I talk about often: seek out what you don't understand. I know it’s so hard. I know we’re wired to avoid things that are difficult and confusing… But our brains actually love the exercise that comes from confronting things we don’t know.